Do I need to cut out an exercise or a whole movement like sit ups? Conclusion

So we’ve gotten some vague opinions suggesting that the sit-up is just terrible… but what about the science???

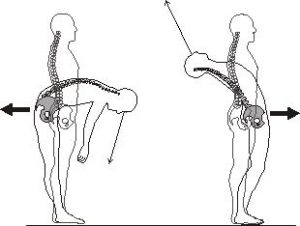

To its credit, the article does eventually get around to bringing in someone whose opinion may be relevant. That someone is Dr. Stuart McGill, a respected spine biomechanics researcher, and I have to say that I’ve found much of his research to be quite interesting. He’s an intelligent and passionate man, and he does lend an air of credibility to the idea that trunk flexion (simplistically, the “forward bending” of the spine which is a likely component of a sit-up) might be something to avoid. Yet once again, the author does little more than invoke McGill’s name (“appeal to authority” fallacy, anyone?) without actually presenting his research and how it might actually show that sit-ups are bad.

The author speaks of how “the forces, combined with the repeated flexing motion, in sit-ups, can squeeze the discs in the spine… [which] can cause the discs to bulge, pressing on nerves and causing back pain, potentially leading to disc herniation.”

Wow. Scary stuff, huh? But wait a minute. What was actually discovered by McGill’s studies? The author links to a brief write-up on the University of Waterloo (McGill’s home base) website stating that McGill he discovered all sorts of nasty loads on the spine during trunk flexion. Modified/alternate exercises are given (which I actually have no problem with, as they may be great for some people). Trouble is, the force numbers given are meaningless without context. What are the capabilities of the tissues? What forces would other exercises cause? Evidence is still not given in this link.

Furthermore, the link mentions “spine specimens” and “modeling approaches on real people” as having shown these results. That’s all well and good. But what does this mean? It seems to suggest that he’s using cadaver spines as his specimens. These are exposed to repeated bending over a relatively short period of time (exceeding the rate at which a living person would likely experience these stresses AND ignoring the ability of a living spine to heal and adapt to stresses over time). Furthermore, these spines are typically taken from pigs. While similar to those of humans, they aren’t identical. An argument could be made that the tissues could have important tolerance differences. Then there are models which, while very useful, are still not definitive evidence that a particular movement is likely to lead to pain or dysfunction in a given individual.

Now I am in no way trashing Dr. McGill’s work (his faculty profile and publications list can be found here). I’m merely pointing out that one has to keep the limitations of any study in mind. It is also worth considering that this researcher has made his career on a body of research that might encourage a little confirmation bias. My feeling is that he probably made up his mind a long time ago that sit-ups were bad, and he hasn’t been completely objective in his subsequent analysis of the topic. I could be wrong, but it’s the impression that I get.

Perhaps one of the most important lines in this entire article comes right as the author starts talking about the “other stuff” that should be done instead of sit-ups. What does she say? Well…

“Sit-ups can be done in many ways, including crunches and sit-ups on stability or Swiss exercise balls. The injury risk with modified sit-ups depends on the exact motion and on an individual’s physical limitations. “

I suspect that she doesn’t realize it, but this author has just taken much of the wind out of her own argument with these two sentence. Sure, she mentions right after that “…some fitness instructors have ditched even modified sit-ups,” but this doesn’t constitute an argument. Just that some people — whose expertise we have no idea about — don’t like a particular exercise. Not a strong point.

A number of exercises are mentioned as alternatives, including planks. The author mentions a paper by an officer for the physical education department at the U.S. Naval Academy in the Strength and Conditioning Journal that advocates looking at the plank as a replacement for the “curl-up” (something like a crunch) on the speculation – yes, speculation – that the curl-up might be leading to lower back injury. Last I checked, speculation wasn’t evidence.

And then there’s the issue of this having been published in SCJ, which is not exactly a bastion of high-quality scientific evidence. It’s home to far more editorials and opinion pieces than most science journals that I’ve seen. This doesn’t necessarily make it without value. We just have to understand the limitations of the source. It’s also worth mentioning that the speculation about lower back injury is likely taken from survey data (as it was in this U.S. Army study which the author also felt supported her position). Questionnaires are notoriously unreliable and shouldn’t be considered strong evidence of any sort of causality at all. Even if the results of the questionnaire were accurate, the research paper admits that, “History of previous injury was a significant risk factor for injury.” This isn’t surprising for anyone who’s spent some time studying back injuries.

The article continues to harp on the (now tired) argument that military appropriateness is supposed to mean something for the general public. I don’t understand why, as it’s a nonsensical argument to make for reasons I’ve already outlined. More unsubstantiated claims, anecdotes, and blatant appeals to authority to pad an essentially empty argument are tossed in for good measure. But at the end of the day, there’s no competent argument being made here for striking the sit-up from one’s repertoire. Just asinine quips about how the sit-up is “outdated” and how so-and-so doesn’t like doing them. The article ends with a series of statements that again actually draw the author’s own argument into question, as they note that there isn’t actually evidence showing that sit-ups cause back pain and that people should focus on exercises that they enjoy and can continue doing. Doesn’t that sound like a familiar sentiment?

So what does this all mean?

Ultimately, it’s all about risk versus benefit. And that will depend on the individual, as every person has different preferences, tolerances, mechanical opportunities based on their structure, etc. An exercise that might be too risky to justify for one person might be completely fine for another. While your grandmother might not be in the best shape to handle a game of pick-up basketball (or heck, maybe she is!), a 25-year-old with no major injury history who is relatively active can probably handle it just fine. Even McGill himself – at the tail end of an article on the Canadian Armed Forces’ decision about sit-ups – states that some athletes may actually want to use sit-ups to achieve their goals. This, coming from a guy who’s probably the most “anti-trunk-flexion” name in the world of exercise science (at least as far as I know).

“Ultimately, it’s all about risk versus benefit. And that will depend on the individual, as every person has different preferences, tolerances, mechanical opportunities based on their structure, etc. An exercise that might be too risky to justify for one person might be completely fine for another.”

Most of the data showing potential harm to the spine are either extrapolated from models that are not also looking at the risks of other exercises or are only looking at one possible way that the exercise is performed; OR they come from studies of cadaver spines which have issues I mentioned earlier. These are, in my opinion, major methodological flaws. Many of the statements about the apparent risk of sit-ups for causing low back problems don’t actually establish if there’s a causal or merely correlational relationship between the two. This doesn’t mean there isn’t some risk – there’s always risk. But I don’t think it’s nearly as bad as the author (and Stuart McGill himself) seem to think.

So while at first glance there seems to be a strong case against ever using the sit-up, a closer look reveals that things are a lot grayer. And that’s how exercise usually works. The answer to most questions is, “It depends.” Can you tolerate the loads? Do you like this exercise more than that? Is it something that you can sustain over time? Does it provide an adequate challenge to your body to achieve the goal?

If the answer to those questions is “yes,” then you probably don’t need to worry TOO much (granted, some of those questions might be harder to answer than others). So don’t fear the sit-up unnecessarily. Just like you shouldn’t fear ANY exercise without good reason.

Even if the Wall Street Journal says otherwise.